borderlands

görlitz, aachen, and the edges of germany

I have been thinking a lot about borders recently.

One reason is that I watched Katya Adler’s brilliant BBC documentary, Living Next Door to Putin, in which she travels along the length of Russia’s border - from Poland to Northern Norway - and talks to ordinary people about life on the front line of Russia’s potential westward expansion into Europe. The border in Adler’s documentary is a boundary: the final edges of normality on one side, and the threat of the unknown lurking on the other. Some of the border spots she visits are highly militarised and patrolled, a no-man’s buffer land stretching out from where west becomes east. But in arctic Norway, on a frozen lake outside Kirkenes, the guard is a teenage girl on a snowmobile, and the border is marked only by coloured poles. In the second episode, Adler takes to the sky in a hot air balloon, and as she stares down at the vast expanse of snow-covered hills and candyfloss skies stretching into the distance, she can only point vaguely at where Finland melts into Russia.

Another reason is that I’ve been feeling stressed about the EES, the new Entry/Exit System which the EU is rolling out starting from today, gathering biometric data on third-party nationals (wince, that’s me), making it easier to monitor time spent in the Schengen area. The stress is mostly practical - I’m going to Frankfurt on Tuesday and have been trying to work out how early I need to leave to navigate the inevitable extra queues at the border - but it’s emotional too. Because behind the instruction to scan my fingerprints, there’s another reminder: you’re not one of us, this is no longer your place, you can come in but you can’t stay. It’s another complication, another cloud, cast over something that used to be so easy.

Border control is tedious, at least from a passenger point of view. We know this: everyone who has ever been to America has a story about being barked at by a homeland security staff; everyone who has ever flown to a mediterranean holiday spot knows how your energy seeps out of you when you step off the plane and into an endless queue, so long that you wonder whether the holiday is going to be worth this. When I arrived in Gothenburg two weeks ago I was surprised to have to show my return flight booking at border control: surprised because I’m not used to airports, and they never ask for it on the Eurostar. And there it was again, the wave of rage and grief and disbelief that Brexit happened; that this border wouldn’t have affected me five years ago and now it does.

(And yes, there are lots of things I am not saying here: that all of this is a thousand times more difficult for people whose movement is restricted by arduous visa requirements; that rhetoric about borders and controlling them is already venomous and divisive; that there is so much injustice in the world that comes down to who is allowed to be where. Other people write much more articulately about these things than I would. How I feel about Brexit is more of a personal mourning than a systemic outrage: I am grieving something I used to have, which was taken away from me).

But! In August I was in Germany - but I was also in Czechia and Poland and the Netherlands and Belgium. From Germany, you can cross borders and hardly notice it. Germany is a good place to visit if you’re interested in borders, because it has so many of them. And without particularly planning it to be so, our visit became a tour of the edges of Germany, from its easternmost city, Görlitz, to its western edge two days later.

We were staying with friends in a tiny village in the east of Saxony, a short drive from both the Polish and Czech borders. It’s a place that doesn’t feel German so much as Central European. You have to carry your passport with you in case the police stop you on the way back into Germany from the east: they shouldn’t, but the AfD is popular in this part of the country and anti-migrant sentiment is on the rise. At first glance, there is very little discernible difference either side of the borders: the road signs change, but the buildings, and the trees, and the light do not. You start to notice the changes once you go indoors: into a Czech restaurant, for example, where you’ll pay £12 for a three course meal and a beer; into a Polish supermarket which, unlike its German counterparts, is open on Sundays; into a café where the waitress might speak a little German or English, but you can’t be certain of it.

The most amazing example of a soft border is the city of Görlitz, in the very east of Germany. It’s one of Germany’s most beautiful cities, with a magical old town built up of winding cobbled alleyways and a glorious gothic church perched high on a hill. But what makes it so special is the river Neisse and the bridge that crosses over it: somewhere on the middle of that bridge, you leave Görlitz, Germany, and arrive in Zgorzelec, Poland. We crossed the river and ate in a waterside restaurant on the Polish side, where we paid astonishingly little for a hearty lunch, and looked out at Saxony - a whole different country - while we ate it.

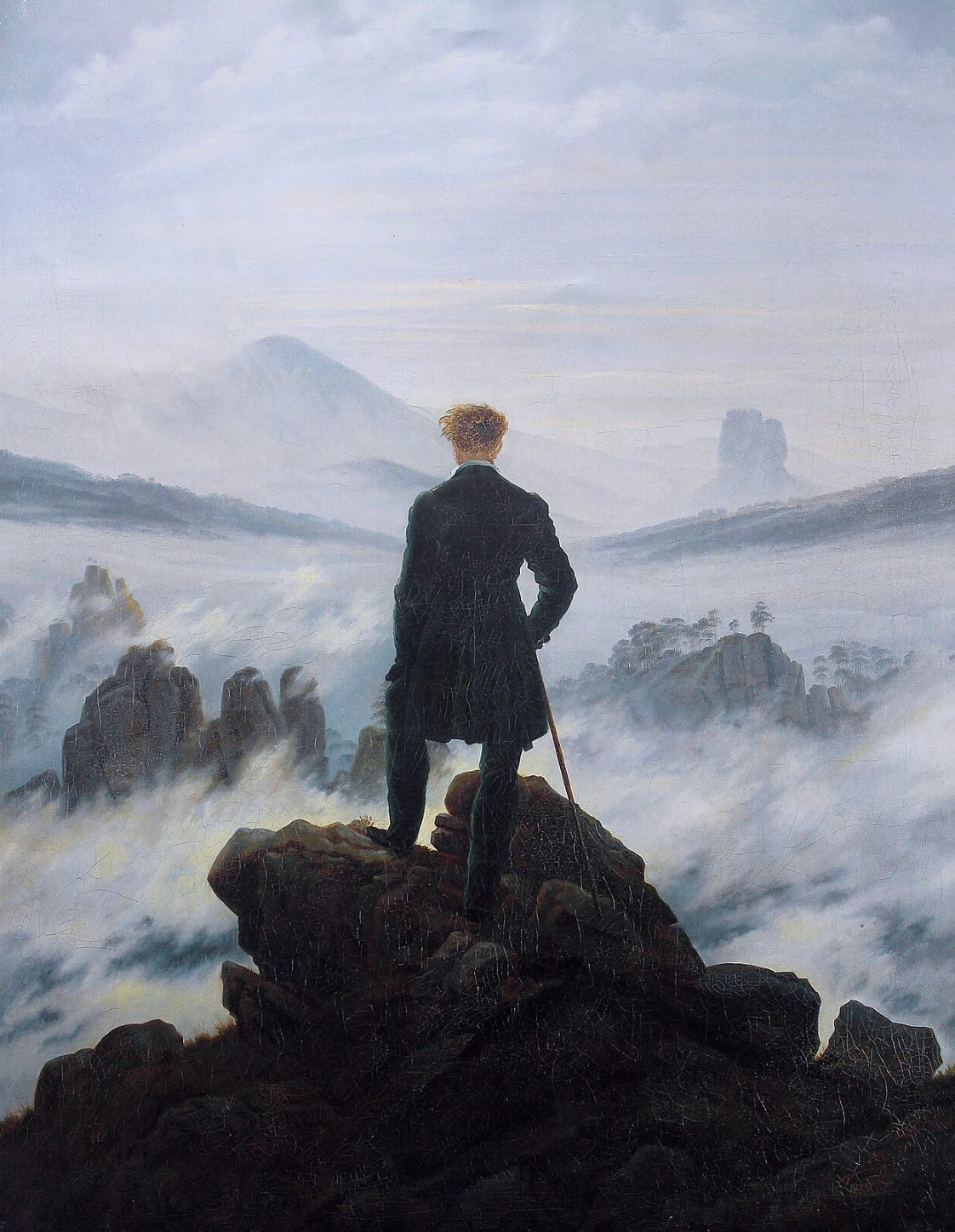

My favourite place in Germany - and a strong contender for my favourite place in the world - is the Nationalpark Sächsische Schweiz, a soaring rocky canyon east of Dresden, marked by sandstone cliffs, and endless foliage far below. It takes in the Malerweg, or the painter’s trail, an iconic walk from the city of Pirna into the mountains, made famous by Caspar David Friedrich and his famous painting. It’s also home to the iconic Basteibrücke, a stone bridge which connects some of the tallest of the rocky pillars, and which either feels surprisingly solid or terrifyingly vertiginous, depending on how brave you’re feeling. From the bridge, you feel as if you can see forever, the Elbe tracing its path in the foreground and beyond that, Europe and Europe and Europe. And, like Katya Adler in the hot air balloon, there’s no way of knowing where one country ends and another begins.

On the way back to London, we stopped for a night in Aachen. You can get from rural east Saxony to London in a day by train, and every time I’ve made that journey, I’ve wondered about the smaller cities we pass through without disembarking: Essen, Fulda, Liège. I’ve stopped in many of the bigger places on the way - Brussels, Cologne, Frankfurt, Leipzig - but it was time to see a little more of what lies beyond the train window.

Arriving in Aachen after a week in Saxony is like arriving in another country. Everything looks different: there’s an idiom to the buildings that feels much more Dutch, or even British, than German. Or at least, it feels more like the Netherlands, or like East Anglia, than the Germany I know. None of this should feel surprising: of course there’s a unity between Aachen and Maastricht and the flat cities that stretch up through Flanders and eventually look out towards East Anglia - just in the same way that it Dresden and Görlitz feel a lot like Liberec and Wrocław and other nearby Czech and Polish counterparts. And yet it’s Görlitz and Aachen that share a language and a nationality.

I liked Aachen. Its skyline is dominated by its world heritage cathedral, the Aachener Dom, consecrated in 805 A.D. in time for Emperor Charlemagne to be buried there nine years later. Beyond the cathedral, the city centre is a jumble of gently sloping alleys, with cobbles and pastel-coloured buildings that reminded me of Norwich’s Elm Hill. We ate Lebanese Mezze at a table in the street outside a lively restaurant, and found a Biergarten full of people much younger and cooler than us.

The next morning, I woke up early and lined up at the start of Aachen’s Lousberg parkrun. The course takes you on two wiggly loops through woodland, high above the city, mud and roots underfoot and plenty of steep bits. It’s not a course for a PB. I ran it slowly, because that morning I’d looked at the map and discovered just how close we were to the border. I finished parkrun, and scanned my token, and then I kept running: through Aachen’s suburbs, through leafy residential streets and a hospital campus and over a ringroad. And then, halfway down an unassuming high street, the posters in shop windows changed from German to Dutch. The paving stones changed colour, and a navy sign with yellow stars let me know, mid street, that I’d arrived in the Netherlands. I bought a coffee from a Dutch coffee shop, and I caught a German bus back to my German hotel room to shower and check out. I’d run between countries, and the most striking thing about it was how easy it would have been to not notice.

Getting there

Start with the Eurostar from London to Brussels, which takes two hours. Prices vary hugely depending on date and time but start at as little as £35.

I recommend the Euronight sleeper train which leaves Brussels at 7.30pm (ish) and arrives in Dresden around 9am the next morning: you can find lots more details in this post. From there, it’s about ninety minutes on a local train to Görlitz.

If you don’t fancy the sleeper, you’ll need to change at Brussels, then Frankfurt, then Leipzig, then Dresden to make it across Germany - you’ll need to leave very early in the morning and you’ll arrive late at night.

It’s much quicker and easier to get to Aachen: change at Brussels, and arrive ninety minutes later.